This past August I and my siblings buried my father on a windswept bluff above Shell Creek, Wyoming. The son of Western ranchers and pioneers, his family story is the stuff of American mythology. But as with any mythology, I’ve been learning the hard truth that the reality underneath the myth is more complicated. This thanksgiving, as American celebrates the 400th anniversary of that mythological “first Thanksgiving,” I’ve been rethinking my family story.

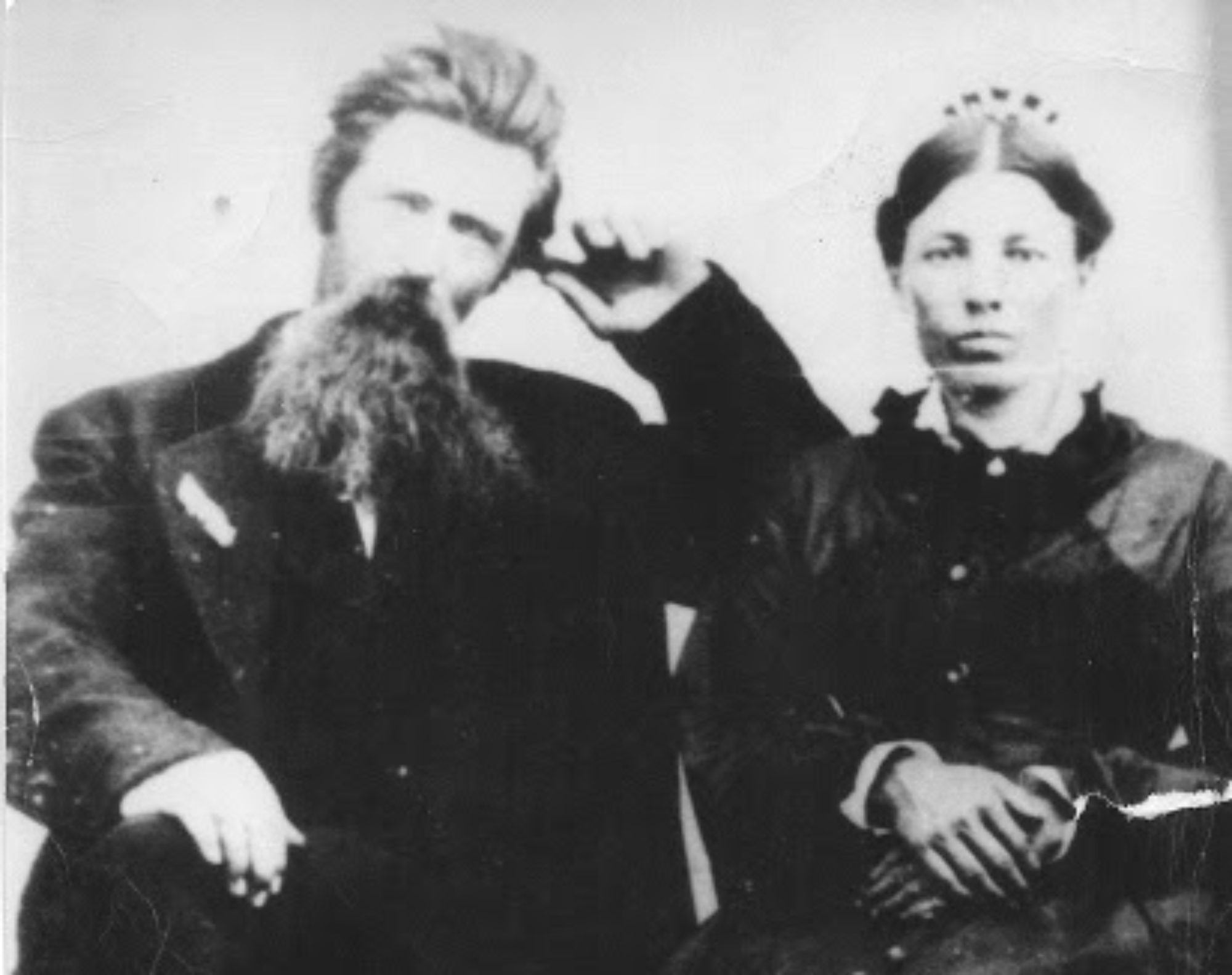

We buried my dad just feet from his parents May and Alois, and a stone’s throw from his grandmother, Charlotte, born in 1867 in the big woods of Pepin, Wisconsin where she grew up playing alongside her famous double cousin, Laura Ingalls. My childhood was shaped by stories of a pioneer family, one with Puritan roots that extend all the way back to Richard Warren who arrived on the Mayflower in 1620 and was a signer of the Mayflower Compact. Like many children, I loved the Little House books and the television series loosely based upon them. Yet when we visited family in Wyoming, I felt like I was literally stepping into the story and playing a part.

On visits to my Grandma May during the summer, I vividly remember marching in Greybull’s Days of ’49 Parade decked in cowboy boots, a hat, and my cap gun slung around my waist. I spent hours mesmerized by my Uncle Jim and Aunt Viola’s glass display case with rows and rows of arrowheads found on their ranch. In an ironic twist due to my dad’s job in Bethesda, Maryland, we always cheered on the Washington Redskins, and never with more ardor than the annual Thanksgiving weekend clash with the Dallas Cowboys. In my childhood imagination, parading as a cowboy, wanting an arrowhead for my very own, and cheering on the Redskins against the Cowboys all was disconnected from current realities of native peoples in America. I simply didn’t know any, nor did my family stories or classroom lessons offer me anything different.

Though I can’t pinpoint a specific moment of conversion, I’ve dramatically changed my views on my family story, and the story of this nation. I now cheer Washington’s dropping of the name “Redskins” from their name. Founded as the Boston Braves in 1932, they changed to the Redskins the following year. Their original fight song, sung after touchdowns, included a parody of native speech: “scalp ’em, swamp ‘um; we will take ‘um big score.” Such disrespectful parody continues with sports teams across the nation, perhaps the most prominent example being the world series winning Atlanta Braves baseball team whose fans are encouraged to gesture with the “tomahawk chop” accompanied by a supposed “war cry” chant. In her third novel, Little House on the Prairie, detailing the family efforts to stake a claim in “Indian Territory,” Laura Ingalls Wilder dedicates an entire chapter to the “Indian War-Cry.” As she lays awake listening to “that savage yipping and the wild, throbbing drums,” Pa sat up making bullets by the fire “till he had used up the last bit of lead.”

I’ll never forget the phone call I had a few years ago with native scholar George “Tink” Tinker (Osage), now Professor Emeritus at Iliff Seminary in Denver. I had called to share the news that he had been named the recipient of an award offered by the seminary where I worked at the time. In the course of the conversation, I told him of my relation to Laura Ingalls Wilder, and there was a long, awkward silence on the other end of the line. I don’t recall exactly what he said next, but he shared how painful the book Little House on the Prairie is for him, and described his use of it in his courses over the years as an example of the racism endemic towards native peoples in America. It was actually his own people whose songs Laura describes as “savage yipping.”

Reflecting on her work in a speech at the Detroit Book Fair in 1937, Laura wrote “I realized that I had seen and lived it all—all the successive phases of the frontier, first the frontiersman, then the pioneer, then the farmers and the towns. Then I understood that in my own life I represented a whole period of American history.” What I am coming to understand is Laura—and my family—only represent one side of a whole period of American history. To tell a truer version of our own story, we need to listen to and learn from other sides of the story, including the kind of stories native voices like George Tinker are telling today.

As my family began the drive west from Minneapolis on our way to Wyoming last August, we intentionally began the trip at Owamni, the inventive and beautiful new restaurant by Sean Sherman, the self-named Sioux Chef. We sat at an outdoor table with a gorgeous view of the falls on the Mississippi that the Dakota people called Owamni (whirpool), the namesake of Sherman’s restaurant, renamed St. Anthony Falls by Father Louis Hennepin in 1680 in honor of his patron saint. Sherman’s simple yet profoundly influential concept is to revive the foods of indigenous peoples before European contact.

It has been fifty years since Wamsutta (Frank James), the then leader of the Wampanoaog nation, stood on Cole’s Hill overlooking Plymouth Harbor and the Mayflower to give a speech telling the uncomfortable truth of the first Thanksgiving. On that 350th anniversary of the arrival of the Pilgrims, including my ancestor, the committee who had invited Wamsutta to give a speech rejected his words as “inflammatory” and “out of place.” In fact, he was simply naming the truth: the only factual part of the myth of the first Thanksgiving is that those Pilgrims would not have survived without the food supplied to them by the Wampanoag people. Since that day, native groups have kept “Thanksgiving” as a “National Day of Mourning.”

The United States poet laureate Joy Harjo (Cherokee) writes in the introduction to an anthology of Native Nations poetry, “Our existence as sentient human beings in the establishment of this country was denied. Our presence is still an afterthought, and fraught with tension, because our continued presence means that the mythic storyline of the founding of this country is inaccurate.” For the past couple years, the congregation I serve in Brooklyn has been praying for the Lanape peoples, lamenting their violent removal from the land upon which we live, work and worship, and seeking God’s blessings upon their leaders today. The church itself is in a neighborhood, Gowanus, named for Gauwane, a leader of the Canarsee band of the Lenape. My commitment this Thanksgiving—and one for the congregation I lead—is taking on learning the other sides of the story, complicating our white European founding myths.

The night before we buried my dad, we pulled out an old green wine bottle with masking tape over the cork and a label that said: ’82 Dandelion. Ever the pioneer, my grandma May made her own wine—grape, and, surprisingly, dandelion. My dad had picked this tradition up, making his own version of the stuff in our basement. I’m not sure if this bottle was from dad or grandma, but we were pretty sure it was going to be vinegar after all these years. We’d brought it to pour on the grave, honoring dad’s memory and all our ancestors buried there. But that night, when we tasted it, to our great surprise, it was good—very good. The next day, we each took a good swig before pouring it on the ground now holding dad’s ashes, saying our few heartfelt words of remembrance under an endless expanse of blue sky. I wonder if some people of European descent in American simply don’t want to know a more truthful version of our history because they expect it only to be sour, a distasteful exercise they would rather avoid. My experience, however, is quite the opposite. Like the ’82 dandelion wine, digging into a more truthful American story is actually very good, good in the moral sense, because in such truth-telling, we open a way forward that is better for us all.