Today, February 7th, is Laura Ingalls Wilder’s 155th birthday. She is known globally as a beloved children’s author and chronicler of 19th century American pioneer life. Yet in recent years, the legacy of her Little House book series has becometarnished by claims of racism, due to the portrayal of native peoples. In perhaps the most dramatic example of this, in 2018 the American Library Association removed Laura Ingalls Wilder’s name from its prestigious children’s literature award citing culturally insensitive portrayals in her books. Yet, as I reread these books critically, I find they may serve as fruitful lessons in the debates over difference and belonging now convulsing our diverse nation. As professor of American Indian Studies Amy Fatzinger shows, there is some evidence that Laura intended them to provoke such critical reflection, albeit within the perspectives of the time of her writing, now nearly 90 years ago.

While such debates over difference and belonging in the U.S. have a long history, the current polarization especially between Democrats and Republicans has taken the fight to new levels. Former president Trump took special interest in this fight, forming the 1776 Commission as a self-described patriotic counterpoint to the 1619 Project. Created by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones at the New York Times, the project re-narrates the history of the United States as fundamentally built not on noble ideals of freedom but on an economic model fundamentally based on the enslavement of Africans. Released to coincide with the 400th anniversary of the first enslaved Africans being brought to American shores, the project became caught up in a moment of national reckoning over racial injustice following the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis by Police Officer Derek Chauvin.

As Jamelle Bouie writes, the ferocity of Republican reaction to the 1619 Project signals that the formerly dominant white Christian Republican base now feel on the defensive. In the last year alone, Republicans have proposed legislation in 37 states banning the use of materials from the 1619 Project and other such materials in public schools. But as Robert P. Jones shows in a recent article, the most extreme version of this trend is Florida’s SB 148 or the Individual Freedom bill that states: “Instruction may not utilize material from the 1619 Project and may not define American history as something other than the creation of a new nation based largely on universal principles stated in the Declaration of Independence.” It goes further to say that, in a clause clearly defending white people, ““An individual should not be made to feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of his or her race.”

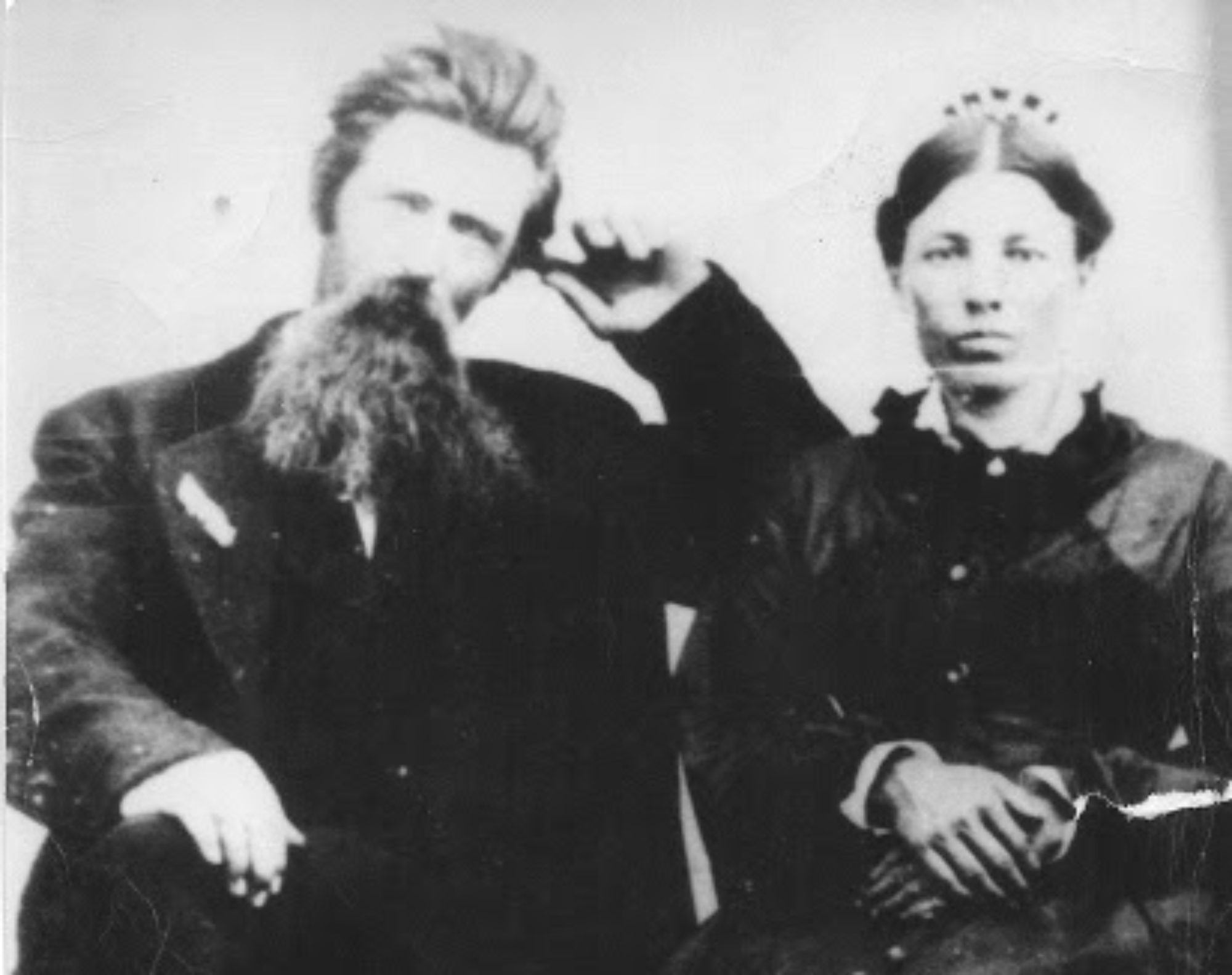

Despite their current reputation, I believe the Little House books might yet be of help as white people—and let’s face facts, that’s who is driving the Republican efforts—learn to be fruitfully uncomfortable with the truth of American history. For many white people, me included, the nation’s history has very personal threads running through our family stories. Both Laura and my great-grandmother Charlotte, Laura’s double cousin, were born in 1867 in Pepin, Wisconsin, movingly described in her first book in the series, Little House in the Big Woods published 90 years ago in 1932. The book, and the seven that followed, are a literal treasure house of American pioneer life and, surprisingly, music. Laura referenced 126 songs and tunes in all. They do all kinds of work in the books—helping bring life to scenes of a festive Christmas dance or a solemn Sunday afternoon. However, at times they also work to make the story more complicated, in just the sort of ways we need to be able to engage today. One instance of this is the song “The Blue Juniata.”

Just now, I am sitting, struggling to pluck out the song on my grandfather’s old Washburn bowl back mandolin. The Juniata (prounced “joo-nee-at-uh”) is a river in central Pennsylvania, and is likely derived from an Iroquoian word, Onayutta, meaning “standing stone.” The ballad is about the “Indian girl, bright Alfarata” and takes place along the namesake central Pennsylvania river, the Juniata. The river was, in fact, the site of major clashes between the Lenape who, driven from their homelands in and around present day New York and New Jersey, had settled on the other side of the Allegheny mountains along the Juniata. By the 1844s when the song was written, the Indian Removal Act (1930) and others acts of congress had forced the removal of the Lenape and other Eastern tribes, mostly to Indian Territory or what is now known as Oklahoma. Today, Oklahoma is home to 39 tribal nations, the legacy of the systematic removal that began in the 17th century with the arrival of English and Dutch settlers along the Eastern seaboard.

As I do research for a book on my family’s story, I’m trying to learn some of the songs referenced in Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House series. I want to feel my way back in time, to feel the steel strings on my fingers, and hear the sounds resonating in my body, just as they would have 150 years ago when Laura describes Pa playing. In a crucial chapter, “The Tall Indian,” in her book The Little House on the Prairie, Laura describes the Indian path running right by their cabin. A tall, gentle Osage man visits, eating dinner and smoking a pipe with Pa before taking his leave. Ma worries, wishing the Indians would keep to themselves, but Pa asserts that he was friendly, and if they treat the Osage well, they’d not have any trouble. Later, after pulling their bulldog Jack out of the path where he was growling at an Osage man on his horse, Pa notes: “It’s his path. An Indian trail, long before we came.”

Then, in a last scene closing the chapter, Pa goes hunting and Ma and the girls unexpectedly find two Osage men at the door looking for food and supplies. Laura describes them as “dirty and scowling and mean”but after taking cornbread and tobacco, they leave. When Pa returns, he shows concern, but says “all was well that ended well.” As usual, as Mary and Laura go to bed, Pa takes out his fiddle and plays, and Ma, rocking in her rocking-chair with baby Carrie, begins to sing softly. Remarkably, Laura, now in her 60s as she writes about this scene from her early childhood, choses “The Blue Juniata” to place on her mother’s lips. “Wild rov’d an Indian girl, Bright Alfarata, Where sweep the waters of the blue Juniata.” In an unusual move, Laura includes the lyrics of the entire song in the chapter because she new it to be among her father’s favorites. In fact, two years after publication, she noted in a letter to her daughter Rose that she’d found a notebook with the lyrics written out by her father, dated 1860, the year her parents married.

As the song ends with lyrics describing the voice of Alfarata borne away, Laura, still awake, raises a question, “Where did the voice of Alfarata go, Ma?” Ma answers, saying she supposes west, because that’s what Indian’s do. Laura, perplexed, pries further. “Why do they go West?” to which her mother says that they have no choice. Unsatisfied, Laura, ever curious, asks why again. Now, Pa chimes in to say, “The government makes them, Laura. Now go to sleep.” Her mind churning after the events of the day, Laura presses her luck and asks for one more question: “Will the government make these Indians go west?” Pa replies that yes, when white settlers come, the Indians have to move on, and the government would move these Indians west any time now. He boasts that when that happens, because they were here first, they’ll get the very best land. Laura, then apparently pressing too far, says, “But, Pa, I thought this was Indian Territory. Won’t it make the Indians mad to have to—-“ and Pa interrupts her saying firmly, “No more questions, Laura. Go to sleep.”

Certainly critiques of the book’s —and the chapter’s — portrayal of native peoples are warranted. She did in fact correspond with the Kansas Historical Society to understand more about the Osage people. But, for instance, in a chapter near the end of the book titled “Indian War-Cry,” Laura recounts laying awake listening to “that savage yipping and the wild, throbbing drums.” Her regular use of offensive terms such as “savage” and “wild” deserve strong critique, as does her regular claims of finding an uninhabited, empty, and thereby available land. the American writer and English professor Gerald Vizenor (Chippewa) calls “manifest manners,” a phrase coined to show how manifest destiny—the assertion that the whole of the North America belonged by divine right to the European settlers—is continued in literature and culture more broadly.

Yet, as I read it, Laura sometimes tutors a critical imagination in her intended audience of child readers. She was exactly right to say her family was on Indian Territory—in fact, squatting illegally on land even Pa admits belonged to the Osage “long before we came.” Pa was also correct in his sense that it would soon be opened to settlers. The Drum Creek Treaty of 1870 did indeed purchase the 8 million acre Osage Diminished Reserve in Kansas for $1.25 an acre, allowing the tribe to purchase land west of the Mississippi from the Cherokee in what is now Oklahoma, and allowing settlers to stake claims to the now available land. But by this time, Laura’s family were already on their way back to their little house in the big woods of Wisconsin. They had learned that the Swede, Gustaf Gustafson, had defaulted on the loan taken out to purchase of their Wisconsin farm, and likely could not have afforded the cost of staking claim to land in Kansas when it finally did become an option.

Marking Laura Ingalls Wilder’s birthday in the midst of such national rancor raises, for me, as a Christian minister and theologian, the question of how to live wisely with this legacy—as a citizen, and as part of her family. I wonder if, as I preached a few weeks ago in reference to Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians, the analogy of the body can help. One part of the body cannot say to another, I have no need of you. And, he continues, if one part of the body suffers, every part suffers with it. For too long, white Christian America has believed itself able to say to some parts of our national body, I have no need of you or your suffering.

For too long, some white people have said, I refuse be uncomfortable enough to actually learn the stories of violence in our shared history as a nation. And the evidence is that some of us at this moment are doubling down on that refusal. In lifting up ways this white history of pioneer life might actually invite readers into a fruitful discomfort about our history, I don’t mean to say that rereading the Little House series is all that is required. Too many of us white people are unfamiliar with native history, and our schools are being forced not to teach such critical facts to inform children to see the history in all its complexity. So discomfort, let alone fruitful discomfort, might mean setting Laura’s Little House books alongside something like Louise Erdrich (Chippewa) and her Birchbark House series, a coming-of-age story of an Ojibwe girl in Minnesota, or David Treuer (Ojibwe) and his magisterial overview of native peoples in North America, The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee. But wisdom, I am coming to believe, means threading a middle path between the naive nostalgia of celebrating pioneer life, and the retribution of cancel culture that would simply put the series on a banned books list.