“Sin was invented by the Christians, as was the Devil, we sang. We were the heathens, but needed to be saved from them: thin chance. ” —Joy Harjo, An American Sunrise

Just before leaving for a road trip from New York to south Texas to visit my mom, I picked up two books to help me understand the 1830 Indian Removal Act: An American Sunrise by the United States Poet Laureate Joy Harjo, a member of the Creek Nation whose people were among those removed from their ancestral lands in Georgia and Alabama to Indian Territory west of the Mississippi, now Oklahoma, and University of Georgia history professor Claudio Saunt’s Unworthy Republic: The Dispossession of Native Americans and the Road to Indian Territory. Harjo’s volume is a powerful multi-genre volume marking her return to her ancestral lands, and Saunt’s a ground-breaking reassessment of the circumstances of the Indian Removal Act.

When I was planning the route south, I was intrigued by a line from Harjo’s poem, “Road.” It ends with “When I returned to these homelands I came by old trails. One of the most traveled trails is part of Interstate 40.” And so it is. Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, in her powerful Indigenous People’s History of the United States, shows the extensive network of trails and roads all over what is now the United States, Mexico, and Central America. Many of these trails and roads guided early Europeans in finding the most advantageous routes, and eventually these became our current roads, even being built into our Interstate Highway system.

We planned our route to travel Interstate 40 and made a stop-over for the night in Chattanooga, a place of ancient significance for Native peoples (going back at least 10,000 years). From the 1700s it was a Cherokee town, that is until the city was incorporated in 1839, literally the year of the removal of the Cherokee by the US government under threat of death. Moccasin Bend, a U-shaped bend in the Tennessee River, and the current site of the city of Chattanooga, however, now is the location for the city’s waste treatment plant and a regional hospital for the mentally ill. Despite its unique importance, it did not achieve protected status as a National Archeological Site until 2003. However, lack of access and existing development on the land have hampered access to and curation of the Native history and culture of the area. One crucial story to be told here is how in the 1830s Cherokees and other Southern Native Americans were rounded up and held here in an internment camp before beginning the “Trail of Tears” march across the south to Indian Territory.

A bit East in Chattanooga, where the Citico Creek empties into the Tennessee River, is the ancient Citico site, one of the largest Native towns in the North America at the time of European invasion and colonization era began in the 15th Century. However, literally nothing remains of this ancient city and its huge mound. The sacred mound was simply excavated as road fill when the Dixie highway was built going east from Chattanooga along the river. It is now the site of the Boathouse Rotisserie & Raw Bar.

The genocidal “total war” on Native Americans from Columbus up till today means such sites of erasure literally are everywhere across the USA. As with Interstate 40 or the Boathouse or the Moccasin Bend Mental Hospital, if you are not Native and knowlegable about your people’s history, as with Ms. Harjo, you have to do some investigation to know anything was there before. So when, in McGirt vs. Oklahoma, the Supreme Court ruled this July that the 1866 treaty the Creek signed with the U.S. government is still the law of the land, and thus much of Eastern Oklahoma, including its capital, Tulsa, are literally still “Indian Country” or tribal-owned lands, it was a particularly powerful moment for those descendants of the Indian Removal Act now living on that land.

In her New York Times Op-Ed following the decision, Ms. Harjo wrote:

Writing for the majority, Justice Neil Gorsuch, nominated for the court by President Trump, ruled that because of an 1866 treaty that the Creek Nation signed with the United States much of Oklahoma is still sovereign tribal land “On the far end of the Trail of Tears was a promise. Forced to leave their ancestral lands in Georgia and Alabama, the Creek Nation received assurances that their new lands in the West would be secure forever. In exchange for ceding ‘all their land, east of the Mississippi River,’ the U.S. government agreed by treaty that ‘the Creek country west of the Mississippi shall be solemnly guaranteed to the Creek Indians’.” All day, I kept thinking how this decision was girded by centuries of history; how the news would be received by the parents, grandparents and great-grandparents who have left this world. The elders, the Old Ones, always believed that in the end, there would be justice for those who cared for and who had not forgotten the original teachings, rooted in a relationship with the land. I could still hear their voices as we sat out on the porch later that evening when it cooled down. Justice is sometimes seven generations away, or even more. And it is inevitable.”

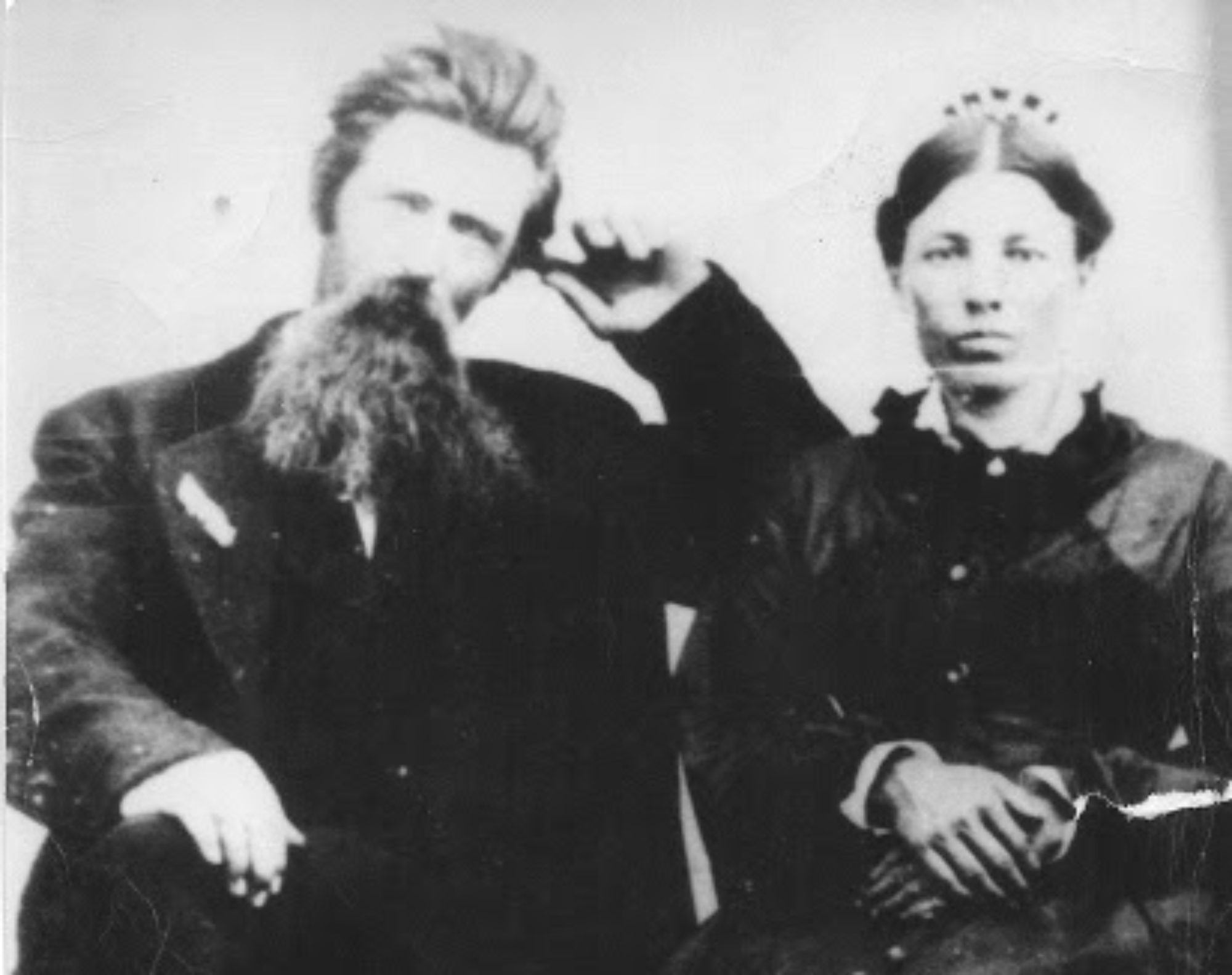

Yes, I felt myself saying along with her: justice is sometimes seven generations away. I’m five generations away from Little House on the Prairie, the stories capturing my family’s mythic pioneer tales of homesteading on Native American land in a story as old as our nation. The 1830 Indian Removal Act and its legacy remains one of the most horrific stains on our history as a nation –and by “our” I especially mean those of us of European heritage.

It turns out the real “heathen,” rather than the “merciless Indian savages” as they are described in the Declaration of Independence, are we white European colonial settlers who built this nation on genocide and land theft, and justified it largely by appeals to Christian doctrine. This project, After Laura, is grounded in this work: telling the complicated truth of this history, and its impact on the shifting dynamics of the nation today, so that we as a whole people might envision a more hopeful future.