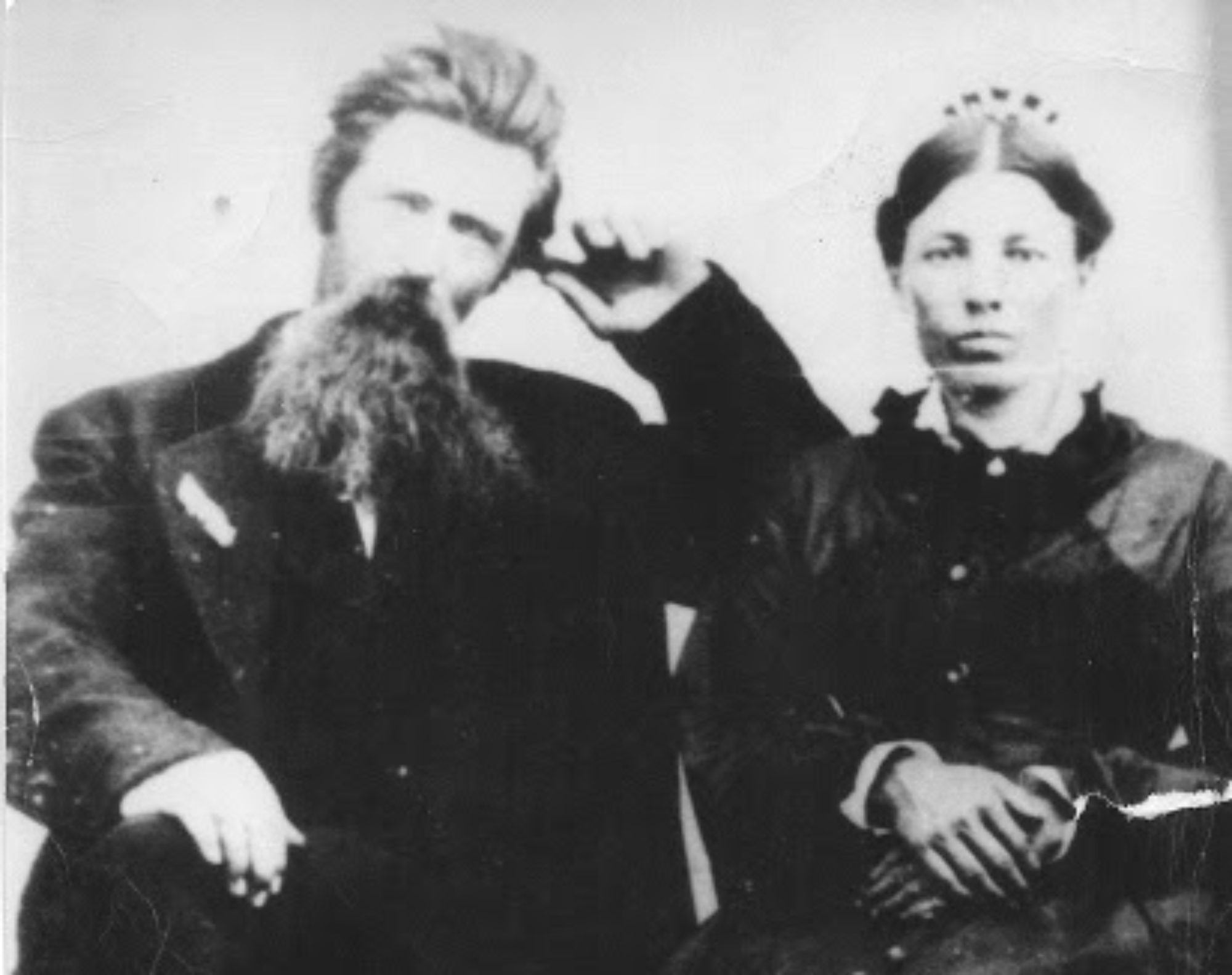

A picture of my great grandma Charlotte ‘Lottie’ Quiner, with her brother James and sister Louisa. Laura Ingalls was their double cousin

One doesn’t begin an investigation of one’s “whiteness” lightly. Yet for the rest of my now middle-aged lifetime, the United States of America will continue its path through a dramatic transformation that will soon see white people become the minority. In a number of states and many cities, this is already the case. One way this plays out is reactionary, sparking a culture of fear and resentment among white people that Donald Trump so effectively tapped in becoming the ‘first white president’ (Nell Irvin Painter). Another way this plays out, suggested near the end of my friend Robert P. Jones’ excellent book The End of White Christian America is to ask, can white people shift from expecting to decide who gets a seat at the table, to simply taking a chair at the table along with everyone else? To make this shift, I’m convinced, people who believe themselves to be white (an invented category, more on that to come) must tell a more truthful story about our past. This site, and the book it will lead to, is my effort in doing this in relation to part of my own particular family story.

Why is my story a ‘white’ story, and what connects it to Native peoples’ trail of tears? After Laura tells the story of my great grandmother, Charlotte Quiner, and her double cousin, Laura Ingalls. They were born the same year, 1867, in Pepin Wisconsin, spent their early years together, and reconnected as teens in South Dakota where their families finally settled years later. Laura’s little house books are iconic literature from America’s pioneer days, read and loved by millions around the world. yet the very fact of their pioneer life depended on theft of land from, and genocidal terror against, the native peoples they called “savages” and “wild animals.” Their divine right, so they felt, to ‘claim and civilize’ this land is rooted in a much earlier set of events, all important aspects of a more truthful telling of my white story. One earlier scene, one that will feature prominently in the work ahead of me, is the 1830 Indian Removal Act. Claudio Saunt’s new book, Unworthy Republic, is a recent and very helpful investigation of how and why in that moment the United States policy towards Native peoples shifted from assimilation to forced removal–the Trail of Tears from the southern states to west of the Mississippi river. Make no mistake, both policies were genocidal, one with its violence cloaked in benevolence and condescension, and the other with its violence cold and bare. more on the Indian Removal Act and Saunt’s book in my next post.